Quite frequently, someone I am enjoying time without outside will say something like “look over there by that pine tree.” Unfortunately, being the dork that I am, I am likely to look around and say “what pine tree?” Some of my friends have gotten clever enough to say “by that conifer”, or “by that evergreen”, thus releasing themselves from any obligation to get a tree identification perfect, and releasing me from dorkhood.

With that in mind, I decided to put together a little blurb on how to tell the different conifers apart. Fortunately, in the Valley, at least in the wild Valley, that isn’t too hard; there are really only 7 species in 5 genera to deal with… actual pines (2 species), true firs (1 species), Douglas fir (1 species), spruces (2 species) and juniper (1 species).

What they all have in common is needle or scale-like leaves, and (except for the juniper) reproductive structures that are obviously “pine cones”.

So here we go:

The actual pines, genus Pinus. Overall, there are 49 species of pines native to North America, but only three in the Valley (lodgepole pine, limber pine, and whitebark pine). They are easily told apart. As pines, all have needles borne in groups (fascicles), more or less joined at their bases.

The most common numbers of needles are 2 (as in P. contorta) or 5 (as in P. flexilis and P. albicaulis). Up close, this is easy. From a distance, the fact that the needles are longer than other conifers makes them look more like bottle brushes.

Get used to the needles first, then stand back and look at the trees and where you are. Before long they will be so obvious to you, you will wonder what the problem ever was. (see also Pinus flexilis, Pinus contorta and Pinus albicaulis ).

The true firs, genus Abies. There are 7 species of Abies native to North America, but only 1 in the Valley. They are incredibly easy to spot from a distance because of their narrow, very pointed crown. If they happen to have cones, that too is a really obvious sign, in that unlike all the rest of the conifers, the cones stand up from the branches rather than hanging down.

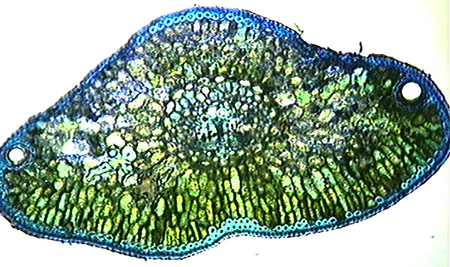

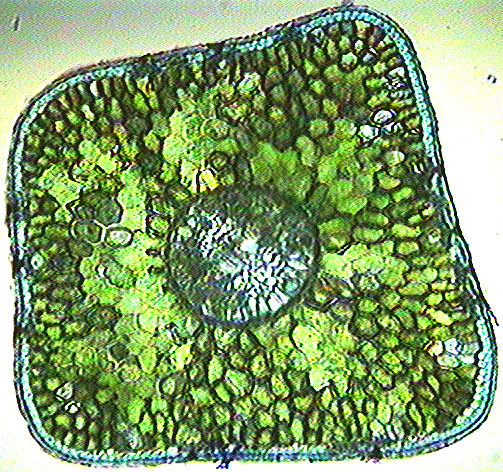

The needles are also good clues; they are flattened so they don’t roll between your fingers. They are also connected straight to the twigs without petioles or pegs of any sort. And they aren’t pointy and sharp like spruce (see Abies lasiocarpa)

Douglas fir, genus Pseudotsuga. This not a true fir, but in a completely different genus. Like the fir, however, the needles are more or less flattened and won’t roll between your fingers.

The needles are connected to the twigs by petioles (but no fascicles or pegs). The needle distribution on the twigs can be a bit confusing; they can either surround the twigs or be two-ranked (i.e. flat rows on opposite sides of the twigs). The twig buds are large, quite pointed and lustrous brown.

What you can really rely on, however, is the cones, and you can often find some of these under the tree or on the ground nearby. The key is that they have trident (three pointed) bracts, like little mouse tails, sticking out from under the one scales. (see Pseudotsuga menzeisii).

Spruce, genus Picea. There are two species of spruce in the Valley – blue spruce (Picea pungens) and Engelmann spruce (P. engelmannii) – and they look a lot alike, even grading one to the other. Indeed, many authors note that not infrequently, it can be nearly impossible to distinguish between them. The Southwest Colorado Wildflower website, however, provides a good summary chart which I will use to give us all a better chance here.

First, however, the genus itself can be distinguished from the others Pinaceae by their needles and cones. Like the firs and Douglas fir, the needles occur singly, not in fascicles. In Picea, however, they are attached to the twigs by short, woody pegs (sterigmata). They are also uncomfortably pointy; blue spruce is downright awful.

In both species, individual needles are 4-sided and will roll between your thumb and fingers. The cones are at the top of the trees and are pendant (hanging downward). The scales are thin and completely unlike pine cones. And there are no mouse tails sticking out from under them.

To decide which of the two species you are looking at, try this:

- Check the needles tips – while all spruce needles are somewhat spiky, the blue spruce needles are nastily sharp, Engelmann spruce less so

- Needle color – totally unreliable and useless in distinguishing species

- Blue spruce twigs are smooth while Engelmann spruce twigs are hairy. This may, however, only be discernible with a hand lens

- Epicormic branching is rare in Engelmann spruce; the trunks are clean between branches. Epicormic branching is often extensive in blue spruce

- Blue spruce trunks often have hard, vertically-ridged bark (and the epicormic branches); Engelmann spruce trunks usually have flakey, scaley bark

- Engelmann spruce is well adapted to higher and drier sites; blue spruce “likes” moister sites (stream sides) at lower elevations

- Engelmann cones max out at about 2.5 inches long; blue Spruce cones start there. Engelmann cones fall off after seed maturity; blue Spruce cones hang on until the next spring (at least).

- On older trees, Engelmann trunk bark is often cinnamon (orange) and scaled; blue spruce bark is gray and furrowed.

(see Picea engelmannii and Picea pungens)

Juniper, genus Juniperus. Finally, there is a single juniper species, J. scopularum, which is in the Cupressaceae rather than the Pinaceae and doesn’t look at all like a pine and doesn’t have “pine cones”. But it is still a conifer and still evergreen. Juniper leaves – at least past the seedling stage – are like overlapping scales rather than needles, and the cones look more like little blue berries. From a distance, junipers are conical with the branches often reaching to the ground… somewhat like the pseudo “pine” trees sold for model train sets. They tend to practice social distancing, i.e. the trees are usually not very close to one another. You’ll mostly see them on exposed, dry slopes along with mountain mahogany and limber pine. (see Juniperus scopularum.)