Spyrogira spp./ green slime

- unbranched, filamentous green alga

- usually as slimy patches or long “tresses”

- anchors to pondweed by entanglement

- prefers the more nutrient rich waters drained from pastures

Also known as: water silk, mermaid’s tresses, blanket weed, pond scum

For those of us of a certain age, the name Spyrogira conjures up not an alga, but a 1970s folk rock/jazz fusion/metal folk band. The band had no relationship to the current subject, a green, slimy alga. You can tell the difference also but the fact that one of the names is italicized.

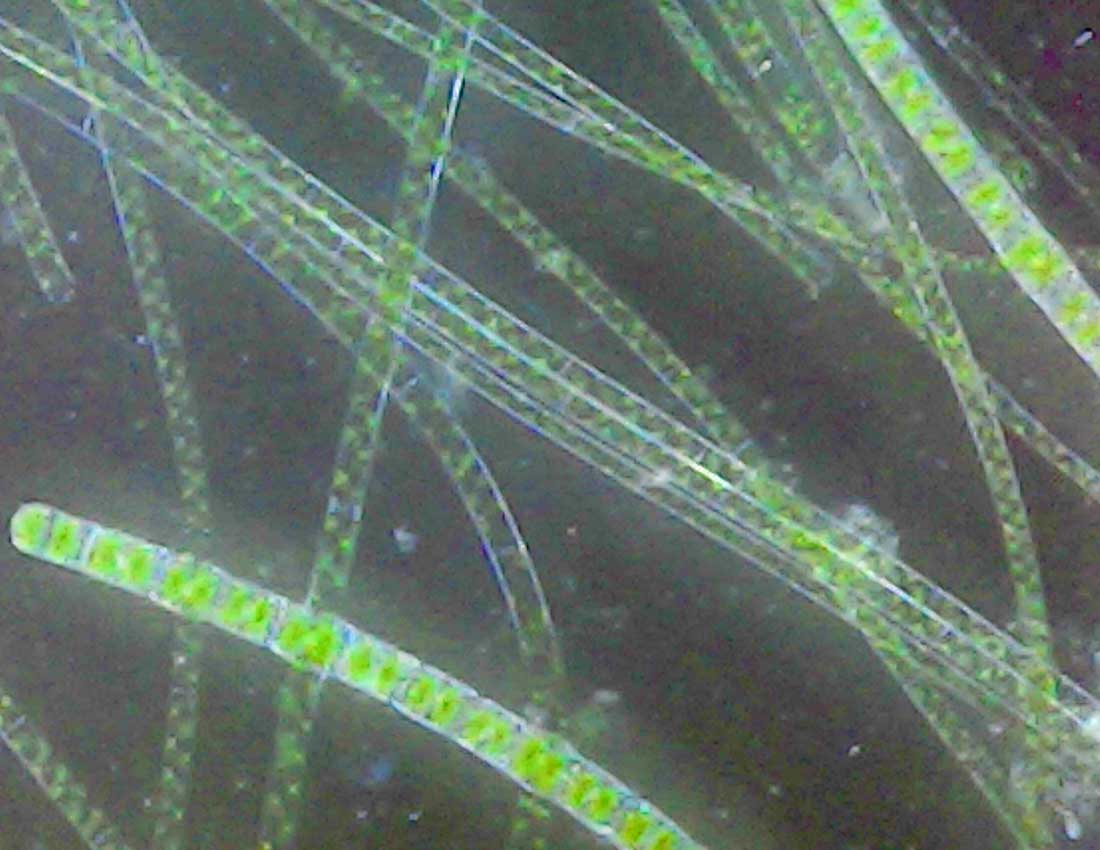

Our Spyrogira is an unbranched, filamentous green alga. All the cells in the filament are about the same size, i.e. without bulges or other bigger cells. The genus was named for the spiral arrangement of its chloroplasts. These sort of show up in the gallery images. Overall, there are some 400 species around the world, and I suppose there is someone who can tell them apart. Spyrogira is commonly found in freshwater, and it is certainly in the upper Teton River, but as far as I have found, it is more common between Fox Creek and South Bates than further down, at least to Rainey Bridge.

Individual Spirogyra cells are approximately 10 to 100 μm in width and may grow to several centimeters long. The cells are connected at their ends into long filaments. In the Teton River, there are two common ways you’ll find it. The first is just a small green slimy patch floating near the surface or stuck on the river’s edge. The other is as long (several feet sometimes) green patches, seemingly anchored at one end in the pondweed and floating free at the downstream end… like silk, or like mermaid’s tresses. It is usually much brighter green than everything around it.

Spirogyra is most common in relatively clear water with eutrophic levels of nutrients, perhaps explaining why it is not too common and mostly in the really upper parts of the river fed by streams that flow through pastures. Part of the reason it is so green is the chlorophyll, but the mass of filaments also traps oxygen and the bubbles reflect light.

Interesting bits – Spirogyra can reproduce both sexually and asexually. The primary means of vegetative reproduction is fragmentation, i.e. the strands break, float free and the cells start dividing end-to-end to make new filaments.

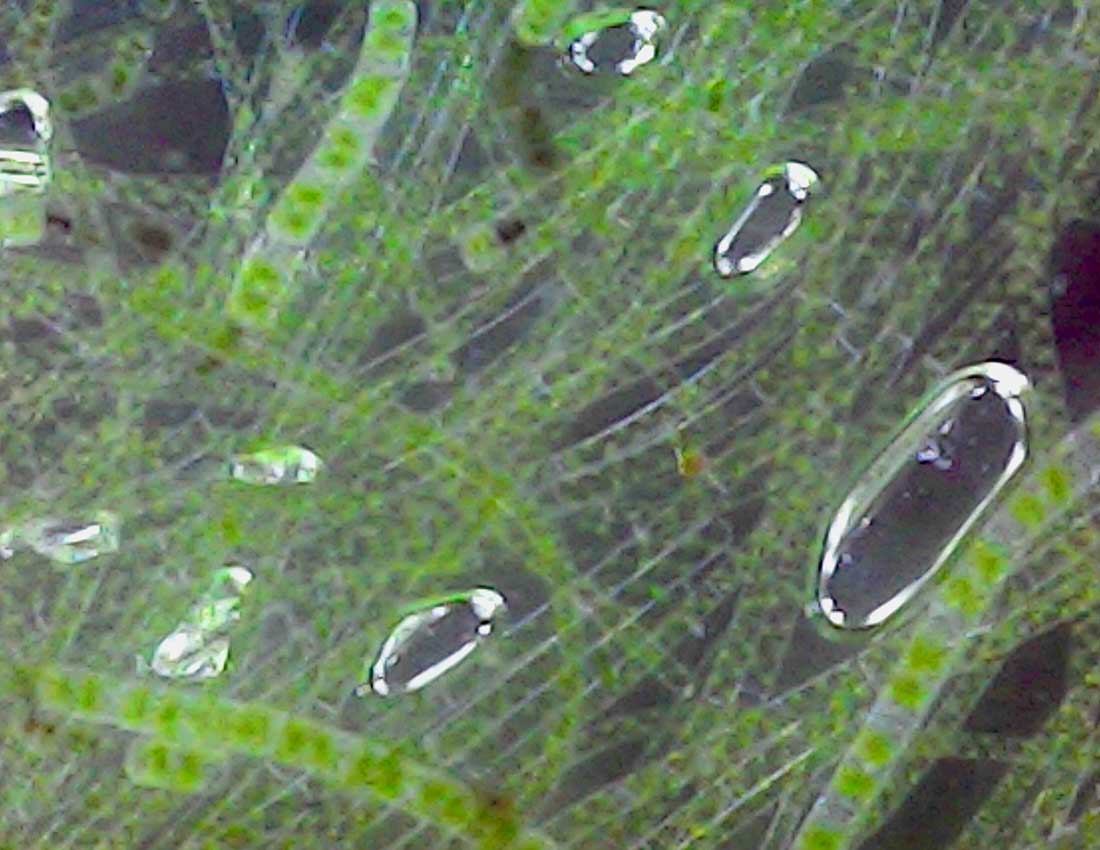

There are two types of sexual reproduction. In the first, called “scalariform conjugation”, two or more filaments line up side by side for some length. One cell from each filament puts out a tubular protuberance, a.k.a. a conjugation tube. One of these acts as a male; the other as female. Tubes from different filaments fuse to make a canal and the cytoplasm from the “male” travels through the tube and fuses with the cytoplasm of the female where the gametes fuse and form a zygospore. It is the appearance of this zygospore that is used to classify species, and they are almost never found in field material.

The other type is also conjugation, but lateral. In lateral conjugation the gametes are from adjoining cells of just one filament. Conjugation tubes are formed between the cells, a canal is formed and the male cytoplasm moves through it to fuse with the female.

The essential difference between the two conjugation types is that in scalariform, two different filaments are involved. In lateral, the events occur between two adjacent cells on a single filament.

Finally, like Chara, Spyrogira provides cover for aquatic insects, snails, and other organisms that fish eat.

| Family | |

|---|---|

| When? | |

| Where? |