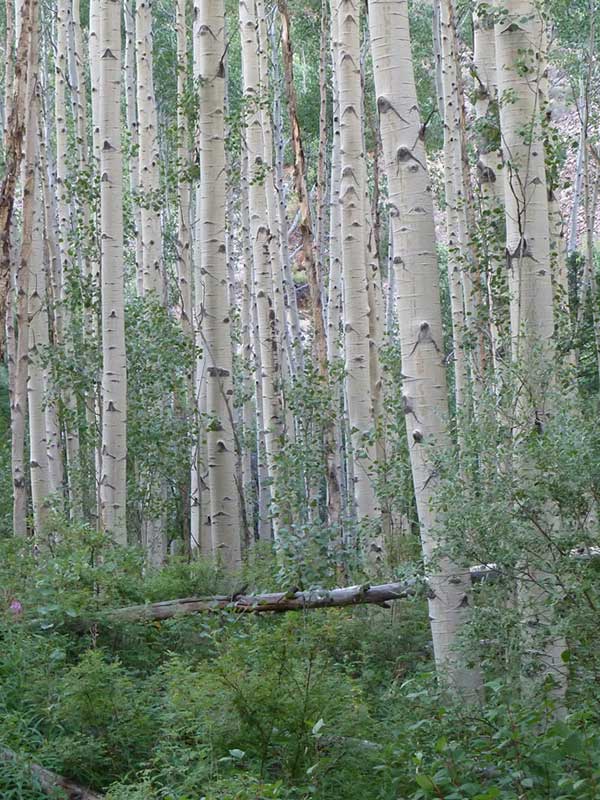

Populus tremuloides / quaking aspen

- white barked, often growing in large clones

- leaves flat with long, flat petiole at 90˚

- leaves quake in even light breezes

- twigs and buds reddish, long and pointed

- catkin flowers in very early spring

- leaves turn yellow or reddish or orange-ish in fall

Also known as: trembling aspen, American aspen, mountain or golden aspen, trembling poplar, white poplar, popple (really?)

Quaking aspens, also called trembling aspens, are named for their leaves. The blades are flat and nearly round. They attach to branches with long, flat petioles which are oriented at 90˚ to the leaf blades. This gives a kind of instability that makes the leaves quake or tremble in even light breezes.

Aspens flower in the spring, the inflorescences being drooping structures called catkins (see photo in the gallery). They are dioecious and wind pollinated. Subsequently, they produce a lot of fluff that contains the seeds, but the life span of an individual seed is measured in hours and the trees seldom actually reproduce that way. Please take note, however… while the pollen can be allergenic, the fluff isn’t. If you feel allergy symptoms at the same time that the fluff is everywhere, look around. You’ll probably find that the acres upon acres of grass in the Valley are also shedding pollen.

Aspens are also unique in many other ways. For example, they have thin, white, or grey-green bark. It is smooth with black areas–like Fu-Manchu mustaches–around the bases of limbs (in old trees, the bark becomes deeply furrowed). If you see parallel vertical scars on the trunk, it is because elk have been browsing there. They strip the bark with their front teeth. In addition to elk browsing, deer and moose seek shade in aspen groves and eat while visiting. Ruffed grouse are especially dependent on these trees for food and nesting places. Beavers have an affinity for aspens as winter food, too.

The bark layer, especially cells just under the bark, carry on photosynthesis. It’s true that that overall carbohydrate production by bark is less per unit area than that by leaves, but it is significant. In winter, for example, aspens continue to photosynthesize when other trees have lost their leaves and gone dormant.

Aspen twigs are shiny and reddish. Soon after the leaves appear, terminal and lateral buds develop on the twigs. The terminal buds are slender, round in cross section, and sharply pointed. Lateral buds often have tips that curl into the branches.

So getting back to the flowers… if they don’t reproduce from seeds, what do they do?

By far the most common means of reproduction is asexual by root suckers. These are stems that grow from roots of older individuals. The combination of all of these adventitious shoots is called a clone. Although they may look like different trees, in fact, they are all genetically identical. A cool and simple way to visualize a clone is to see them in the fall; all the trees in a clone will change color, to the same color, at the same time. They synchronize again in the spring when all flower and produce leaves at the same time.

The simplest place to see this in action is in front yards of houses where aspens have been planted. “Baby” trees are always springing up and if they aren’t mowed, can take over. In open areas, e.g. pastures, you can often see a clone that is tall in the middle and tapers at the edges as new stems expand the clone outward.

In effect, root suckering makes aspen clones immortal. At least I’d consider tens of thousands of years immortal. An individual stem might live 50-60 years. Perhaps up to 150 years in the West. But they keep spreading by root suckers. The oldest currently known quaking aspen clone has a name– “Pando”. It’s located north of Bryce Canyon National Park in central Utah. It has been aged at 80,000 years and is male. Younger clones, only 5000-10000 years, are much more common.

Immortality has other consequences, too. For one, aspen clones are almost impossible to kill (think before you plant one). You can eliminate individual stems, or animals can eat them, or disease can take them down, but the roots live through all that. Your only hope? Pocket gophers. They feed on the roots. You can’t even burn them down. Aspens require full sun to grow and can be shaded out by, for example, spruce, fir, pine or Douglas fir. But when fire comes through, the canopy is thinned and aspens aren’t.

Quaking aspens are the most widely distributed tree species in North America, growing from Alaska to Mexico. They can be limited by temperature, however, so at northern latitudes, they are lower down than in the south. They can withstand air temperatures as low as -78˚F, or as high as 110˚F. They need water, but intermittent springs in the desert provide enough, even when annual rainfall is less than 7 inches.

| Family | |

|---|---|

| Inflorescence size | |

| When? | |

| Where? |